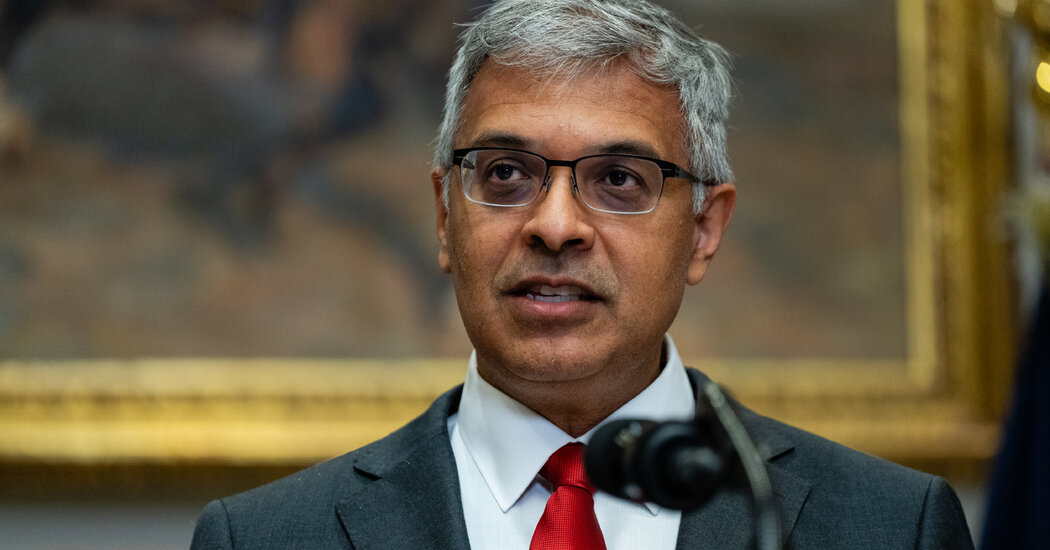

The sun was bursting through the sandstone arch of Window Rock in northeastern Arizona, and Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., in bluejeans, was finally in his element: on a hike.

It was the last day of his multistate Make American Healthy Again tour, designed to highlight various aspects of Mr. Kennedy’s plan to fight chronic disease, such as healthy school lunches and medical clinics that take a holistic approach to patient care.

Now, the health secretary was strolling with the president of Navajo Nation, delegates of the nation’s council and the acting director of the Indian Health Service, discussing the challenges of providing high-quality health care to tribal groups. Here, weaving through the desert brush, Mr. Kennedy seemed to be hitting his stride.

Mr. Kennedy had left Washington with questions growing about his handling of a measles outbreak in West Texas and the firing of thousands of Department of Health and Human Services employees. On his way out West, he had to make a stop in Texas on Sunday to attend the funeral of an unvaccinated 8-year-old girl, the second child to die of measles in this outbreak.

And at the start of the tour the next day, Mr. Kennedy had seemed stoic — maybe nervous, even — as he was led through a Salt Lake City health center focused on nutritious diets. He declined a bag of fresh groceries, citing his upcoming flight. In the “training kitchen,” he dropped an ice cube, dribbled a mango lassi and stood expressionless as a medical student reached to activate the secretary’s food processor without putting the lid on. (An administrator stopped her just in time.)

“That would have been bad,” the student said, glancing at the secretary’s white shirt and pressed suit. At last, Mr. Kennedy cracked a smile.

By Tuesday, Mr. Kennedy had loosened up, wearing a stegosaurus tie and shaking hands with a Navajo toddler at a health center near Phoenix, as the boy learned to cook blue corn crepes. The health secretary poked his head into the refrigerators of a food distribution center, examining food labels and nodding as he said, “Very impressive.”

There was the one minor faux pas, at a 1,300-person tribal conference, when Mr. Kennedy sought to show off his knowledge of the attire of the Wampanoag, many of whom live on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, in Massachusetts. (“My home tribe,” he said.) As he spoke from a glittering casino stage, he pointed out the tribe chairwoman’s traditional shell-bead earrings and necklace and announced, “If you want to know what wampum originally looked like, she is a museum piece!” (She gasped.)

At a news conference on school lunch legislation in the Arizona State Capitol, Mr. Kennedy was flanked by dozens of school children, several of them waving posters with slogans like “Cut the Chemicals” and “Ditch the Dyes.” There was raucous applause, a “Go Bobby!” chant from the back. By then, he was beaming.

Wednesday morning, on the hiking trail, Mr. Kennedy offered a glimpse of the persona he had once displayed on the presidential campaign trail: an adventurous and spiritual man, ardent in his convictions — regardless of their popularity — who had clawed his way out of a heroin addiction by throwing himself into new extremes.

He was the first to scramble to the pinnacle of the Window Rock formation, a silhouette balancing 1,000 feet above the valley floor.

When it comes to his own battle against chronic disease, Mr. Kennedy relies on a natural diet and intermittent fasting, as well as a morning routine including a 12-step meeting, gym time and meditation. But since arriving in Washington, he has had to give up a favorite daily ritual: a three-mile hike with his dogs.

On this trek, officials discussed initiatives like the Navajo Nation’s longstanding 2 percent tax on junk food, adopted as part of legislation passed in 2014 that also removed a higher tax on fruits and vegetables and inspired similar policies in neighboring towns. They also talked about the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry — a tribal program that sells corn, beans and other products under the “Navajo Pride” brand to support the community.

To close his tour through southwestern states, Mr. Kennedy visited Hózhó Academy in Gallup, N.M., a K-12 school that hosts gardening and cooking events for families and uses a curriculum to help students plan their own health goals.

Epidemiologists say there is an array of factors driving rates of chronic disease,including genetics, changes in the intestinal tract’s microbiome and the fact that Americans are generally living longer and therefore facing new conditions that come with age.

Mr. Kennedy has tended to de-emphasize those factors, those experts say, instead focusing on childhood vaccine schedules, psychiatric medications and other variables. But here on the tour, Mr. Kennedy kept most of the attention on personal wellness as a key method for addressing the crisis.

The secretary’s fervor for taking on the big food companies seems to align more with the traditional political left than the right. His fight against artificial food dyes — “poison,” as he called them — is an echo of existing California laws, and his school visits are reminiscent of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign that took on obesity in children.

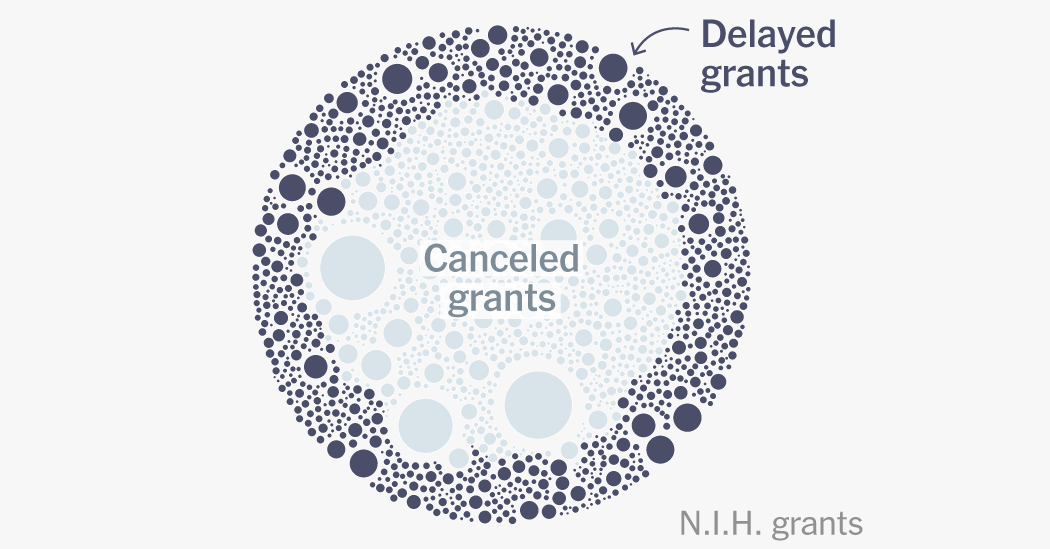

To some, Mr. Kennedy’s championing of healthy food legislation. comes at a paradoxical moment, as widespread layoffs at the Food and Drug Administration last week included lab scientists who tested food for contaminants; the administration also eliminated a key food safety committee and reduced funding for state-based food inspectors.

And as Mr. Kennedy promoted chronic disease prevention, key efforts like the Diabetes Prevention Program, a 29-year-old research initiative, were eliminated. On his descent from the hike, a delegate of the Navajo Nation Council who has struggled to obtain diabetes medication intercepted the secretary and unzipped her jacket to reveal a T-shirt with a handwritten phrase on it: “SAVE I.H.S. JOBS & DIABETES PROGRAM.” (I.H.S. stands for the federal Indian Health Service.)

“A subtle message,” she quipped.

Mr. Kennedy promised her that he would talk to his team and see what he could do. She linked her arm with Mr. Kennedy’s — worried about keeping balance in her moccasins — and kept it there the whole way down.