For a child who is not vaccinated against measles — one of the world’s most infectious viruses — no classroom, school bus or grocery store is safe. Nine out of 10 unvaccinated people exposed to an infected person will catch it, and once measles takes root, the virus can damage the lungs, kidneys and the brain.

With falling U.S. vaccination rates and outbreaks that have caused more than 580 cases and at least one death, health experts expect measles to infect hundreds or even thousands more across the nation. Here is how measles takes over the body.

Unlike viruses that require person-to-person contact, measles lingers in the air for up to two hours after the person carrying it has left the space.

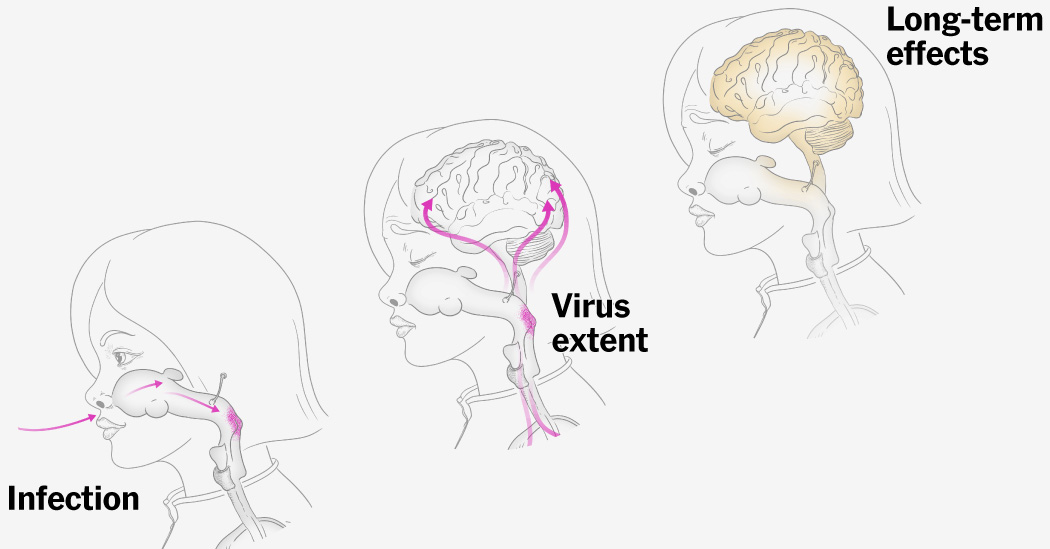

A child can inhale virus-containing droplets in a room where another child — unknowingly infected with measles — has been studying or playing an hour earlier. The virus can enter her body through the lining of her nose or mouth, or when she’s rubbing her eyes.

During the subsequent 24 hours, the virus takes root by lodging in her nasopharynx cells in the upper part of the throat and starts spreading to her lungs.

Then, the virus takes over, multiplying inside the cells and building up an army for an attack.

Within a few days, the virus begins to spread to infect the nearby lymphoid tissues. About a week after the initial exposure, infected cells begin traveling to other organs throughout the body. (At this time, the immune system of a vaccinated child would recognize the virus and fight it off.)

Typically, during the replication and spread of the virus, the child does not feel sick. The average incubation period is about two weeks — though it can range from one to three. When the viral load has increased significantly, it moves to infect other cells of the lungs and eyes, making the child feel ill.

A couple of weeks after the unvaccinated child inhales the droplets, she starts feeling sick.

Children often first show signs of malaise and a fever, followed later by reddish, irritated eyes, a cough and a stuffy nose as the mucus membranes and nasal passages become inflamed.

Some children at this stage develop millimeter-wide, whitish-gray bumps on the inner lining of the cheeks, as far back as the molars. For some, the spots go undetected, or do not show up at all.

Then comes the characteristic feature: the breakout of a red rash, starting on the face and spreading down the neck, trunk, and extremities.

Many of these symptoms should resolve themselves. The rash can last up to a week, often fading along the same route it appeared. The cough can last for up to two weeks after the illness has resolved. But a fever lasting beyond the third or fourth day of the rash suggests that a complication could be developing — and that is where cases can become dangerous.

Even as the rash fades, the infection can spread to the lungs and other organs.

Children are typically brought to the hospital after having the body rash for several days. Most have low oxygen levels and are laboring to breathe and need support, said Dr. Summer Davies, who sees children at Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, and has been treating measles cases there since the outbreak started in late January.

“A lot of families have kind of been surprised, like, ‘Oh, my child was fine, and then all of a sudden, they’re not,’ ” she said.

That mild disease evolves into a fever as high as 104 or 105 degrees for two, three or four days. Poor fluid intake, a sore throat and diarrhea can lead to dehydration, which over time can begin to threaten kidney function.

Young children are more at risk because of their smaller anatomy and their inability to articulate symptoms clearly, explained Dr. Lara Johnson, the chief medical officer of a group of Covenant hospitals in the area.

About one in 20 children with measles will develop pneumonia, an infection in the lungs; and severe cases can be fatal.

Dr. Davies said many children admitted to her hospital recently had cases of pneumonia caused by either the measles virus or by a second pathogen that attacked while their immune systems were weakened.

The 6-year-old girl who recently died of measles in Texas had a case of pneumonia that caused fluid to build up in her left lung, making it difficult for her to breathe, according to a video interview with her parents that was posted online. She was eventually sedated and intubated, but she became too sick to survive.

One of the hallmarks of measles is what researchers call “immune amnesia,” the temporary weakening of the immune system. Measles wipes the protection children have acquired from other infections, which leaves them susceptible to other infections for several months or even years.

Inflammation in the brain

About one in 1,000 children who contract measles will also develop encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain tissue, which can result in permanent damage.

For infants or children who are already immunocompromised, a condition called measles inclusion body encephalitis (or MIBE) occurs when the child cannot clear the infection. It can trigger mental changes and seizures, leading to a coma and death in most patients.

Another type, called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), is a degenerative condition that can occur up to a decade after a measles infection. Children often first show signs of behavior change and academic decline, followed by seizures, motor issues like poor coordination and balance, and eventually death. The mortality rate approaches 95 percent.

Erica Finkelstein-Parker, a mother in Pennsylvania who lost her 8-year-old child Emmalee to the condition, had not known that the girl had had measles before she had been adopted from India as a toddler. But she noticed one day that Emmalee was tripping and falling, slumping over to one side of her chair and struggling to lift her chin off her chest during dinner.

Doctors explained that there was no cure. Emmalee passed away about five months later.