In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed a law — the High-Speed Ground Transportation Act — that seemed to pave the way for a national high-speed rail system in the United States. “An astronaut can orbit the earth faster than a man on the ground can get from New York to Washington,” he lamented at the time. Sixty years later, it still takes about three hours to travel between the two cities — a period about twice as long as a single orbit of the International Space Station.

High-speed rail in the United States is still years away. But projects across the country, from Washington State to Texas, suggest a growing enthusiasm for faster train service. These efforts are relatively modest in size, proposing to connect two or three cities at a time. But that may be precisely what makes them feasible.

Under the Trump administration, high-speed rail is unlikely to receive additional support from the federal government. “There should be a federal program,” said Rick Harnish, executive director of the High Speed Rail Alliance. “But in the current circumstances, states need to do what they can on their own.”

High-speed rail 101

Andy Kunz, president of the U.S. High Speed Rail Association, estimates that only about two dozen countries across the world now have high-speed rail, which he said typically refers to train systems that go at least 186 miles an hour. Almost all of them are in Western Europe or East Asia. The only high-speed rail in Africa is the Al-Boraq in Morocco. There is no high-speed rail in the Americas yet.

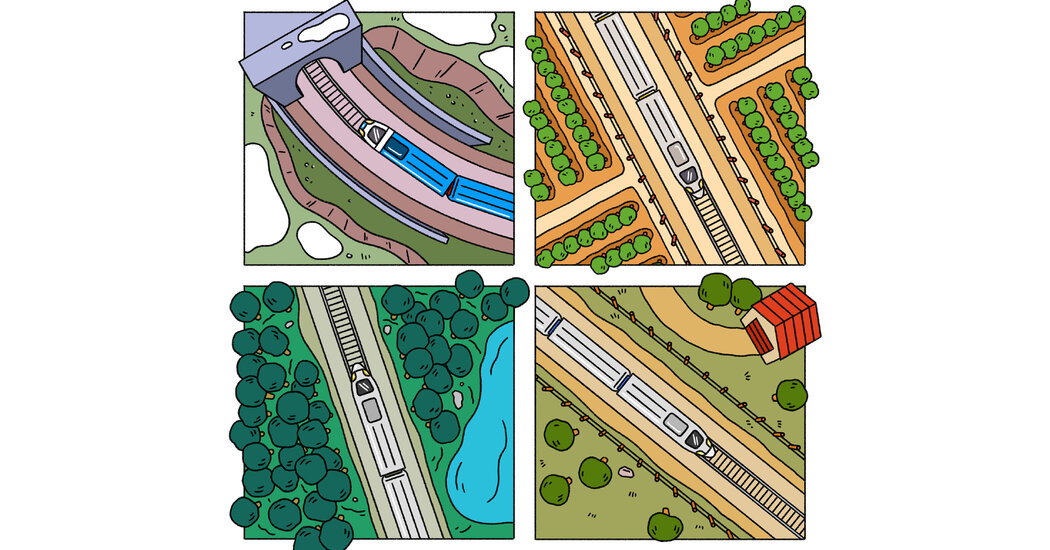

Ordinary tracks cannot simply be repurposed for high-speed rail, Mr. Kunz explained. The speeds involved require a “sealed corridor” with grade separation — features like overpasses and underpasses that prevent cars and pedestrians from having to cross in front of a bullet train. A high-speed train can’t nimbly wend its way through the landscape — it needs long straightaways, gradual slopes and gentle turns.

The fastest trains in the U.S. right now

Right now, the Amtrak Acela train is the fastest rail line in the United States, reaching speeds of 150 miles per hour. Amtrak is preparing to roll out updated NextGen Acela trains along the Northeast Corridor sometime this year. But the new trains’ top speed will be only 160 miles per hour.

Even if Amtrak spends billions on upgrades, Acela will never really be in the high-speed game. That is partly because Acela travels on ancient tracks that pass through dense population centers crowded with other infrastructure. Old bridges and tunnels create choke points. Freight and commuter lines jostle for access. “Amtrak is building a rail system for the 1890s,” said Representative Seth Moulton, Democrat of Massachusetts.

Brightline — the private rail line now running between Orlando and Miami — is the next-fastest line after Acela, topping out at 125 miles per hour. Because it lacks grade separation, accidents have plagued the line. But as Michael Kimmelman notes, Brightline has become a popular option for many Floridians and tourists.

Pending rail projects

Brightline West

In 2024, an offshoot of the company that built the Orlando-Miami train line broke ground on Brightline West, a 186-mile-per-hour train that will link Las Vegas to Rancho Cucamonga, Calif. The line, which is expected to cover 218 miles, will be built on a strip of land between the north- and southbound lanes of the I-15, so it does not have to go through the costly process of negotiating rights of way with private landowners. Environmental reviews are over and done with, and passenger service is expected to begin in late 2028.

“This one is super easy to build, because it’s a wide open desert,” Mr. Kunz explained. “It’s flat,” and few people live in the harsh desert region through which the train will pass.

Read more in Michael Kimmelman’s story about Brightline.

California High-Speed Rail

“California is the first place in our nation where we will see a true high-speed rail system,” Arnold Schwarzenegger, then governor of the state, vowed in 2009. The initial phase of the project, connecting San Francisco to Los Angeles at 220 miles per hour, was supposed to have opened in 2020, and go all the way from Sacramento to San Diego by 2027.

But the troubled project is still many years from completion. For now, the state is focused on a 171-mile trunk through the Central Valley. And though California received $4 billion during the Biden administration, there remains a sizeable shortfall in funding.

At a recent press conference, Rep. Kevin Kiley, a Republican congressman from California, described California’s high-speed rail as “the worst public infrastructure failure in U.S. history.” Tom Richards, chair of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, said that three challenges had proved persistent: the need to acquire rights of way through private property, the astonishing cost of moving various public utilities and the expense involved in passing environmental reviews. But bullet train boosters say challenges have been exaggerated.

“Everyone loves to rip on it in the press, but the project is about one-tenth as bad as they try to make it sound,” Mr. Kunz said. “When that thing actually gets up and running, it’s going to radically change transportation.”

Cascadia

In the Pacific Northwest, Microsoft has partly funded the planning for Cascadia, a high-speed rail line that would connect Portland, Ore.; Seattle; and Vancouver, in British Columbia, at 250 miles per hour. The Federal Railroad Administration has also contributed $49.7 million.

“They’re really organized,” Mr. Kunz said.

But engineers have not decided on a route yet, and planning could take another five years. Bob Johnston, who has covered passenger rail for decades for the magazine Trains, believes that because the Pacific Northwest is already so congested with infrastructure, it may make more sense to improve service on existing Amtrak lines than to build out a whole new system.

“They have the will, it’s just going to be an uphill battle to execute,” Mr. Johnston said of Cascadia’s backers.

Texas Central

In the early 1990s, a company called Texas TGV proposed a high-speed network for the state, only to see its funding fall apart. About a decade ago, Texas Central partly revived that plan with a proposed Houston-Dallas line.

“Then the pandemic hit and everything kind of collapsed — they basically shut down,” Mr. Johnston said. But he believes that the route has many of the same advantages as Brightline West, calling the area the line would traverse “one of the most perfect places where high-speed rail could really work.”

Having evidently come to the same conclusion, Amtrak took charge in 2023. Last year, the project received a $64 million federal grant, and Amtrak is now looking for private companies to choreograph the complex dynamics of turning the projected 240-mile rail line into reality.

The dream of a national system

The dream of a national high-speed rail line is being kept alive by legislators like Mr. Moulton, the representative from Massachusetts. Since 2020, Mr. Moulton has been pitching a $205 billion federally funded high-speed rail system that would connect the entire country.

In an interview, Mr. Moulton argued that connecting two large cities with high-speed rail would also foster better connection among surrounding smaller cities. “If you built high speed rail between Chicago and Boston, it would not only be great for Chicago and Boston, it would be absolutely transformative for Cleveland, for Buffalo, for Syracuse, for South Bend, for Albany,” Mr. Moulton said. “All of a sudden, they’re accessible to these great economies.”

He suggested that by compressing enormous distances, high-speed rail could perform the important work of “truly knitting the country back together.”

When it comes to transit and mobility, what project is changing your community?

The Headway initiative is funded through grants from the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors serving as a fiscal sponsor. The Woodcock Foundation is a funder of Headway’s public square. Funders have no control over the selection, focus of stories or the editing process and do not review stories before publication. The Times retains full editorial control of the Headway initiative.