There aren’t many artists in the last 40 years who’ve been written about quite as much or as fervently as the painter Lisa Yuskavage, who is 63 and based in Brooklyn. On her website, she makes available PDFs of every article in which she’s ever been mentioned, including not just the major interviews and reviews (even the unkind ones) but also reviews of other artists that simply cite her work. The archive begins in December 1985, when a student magazine at Yale published an image from her M.F.A. thesis project. Yuskavage is uncommonly attuned to the weight of public opinion, and her engagement with other people’s takes on her has helped bolster her conviction to make only the art she wants to make, whether it’s met with praise or bewilderment (or worse).

There’s been an ongoing critical debate about Yuskavage’s work because she is a woman who paints women, often nude, in an absurd state of sensuousness. This subject matter alone has, until recently, been suppressed from art history. She deploys the same delicate shading technique (known as sfumato) that the major Renaissance painters did, so that her figures seem to be emerging at the very moment the sun breaks through a morning fog. The paintings are executed with extreme care. They’re also dirty — just a little wrong. The curator Helen Molesworth once wrote about the embarrassment she felt when seeing Yuskavage’s paintings in the early 2000s, and her strong suspicion that “if a white man of a certain age had been the first to show me [her] work, I would have rejected it immediately.” In a New Yorker profile of the artist from 2023, Yuskavage’s former art dealer Marianne Boesky said, “I knew I shouldn’t like her work, but I did.”

During our first interview, in March, Yuskavage held on her lap a copy of “The Silent Woman: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath,” Janet Malcolm’s 1993 biography of the marriage between two of the 20th century’s most famous poets, which is, in Malcolm’s words, an “allegory of the problem of biography in general.” Plath and Yuskavage come from very different generations, but they both wanted to create art that was uncomfortable and shocking — and they’re artists onto whom audiences feel compelled to project their own psychodrama, which is the real subject of Malcolm’s book. Reading it helped Yuskavage come to terms with the idea that she was, depending on which publication she read, “caricaturing women in an ideological shorthand and raping them” (Artforum), mired in “wrenching self-hatred” (Time Out) or making “the best — the craftiest, funniest and, in a dark way, sexiest — art around” (Newsweek).

Lately, many of her paintings, some of which were on view earlier this year at David Zwirner gallery in Los Angeles, have been set against a backdrop of the artist’s studio, another technique originating in the Renaissance. The studios Yuskavage paints are not exactly like her own but reminiscent of it, with big windows and ample space. Hers has a great view of the F and G subway line as it screeches over the Gowanus Canal into the Smith-Ninth Streets station. It’s organized but crammed, full of everything related to her life as an artist. This includes files of rejection letters from teaching jobs and galleries , along with thousands of sketches and drawings, a selection of which will go on view in a solo exhibition at New York’s Morgan Library this month.

In our first meeting, Yuskavage and I spoke for about four hours, interrupted only by a brief call from her husband, the painter Matvey Levenstein, 65, whom she speaks to throughout the day. (He works out of a studio near Union Square.) We continued the interview three weeks later over the phone. What follows has been edited and condensed from both conversations.

M.h. Miller:

Can you tell me about the artist’s studio and why that is something you’ve been painting over the last couple of years?

Lisa Yuskavage:

Artist studios are known to be very special spaces. I’m not saying this one is, but you can decide.

M.H.M.:

For you it is, right? It must be.

L.Y.:

M.H.M.:

You had to do better than they did.

L.Y.:

So that is the world they gave me, which is of course a great gift. But the thing is, you don’t even realize how lonely you’ve been until you find your people. So I think in some ways, these paintings are all a celebration of the most important things in my life. I was a nude model in art school. For money. I didn’t do it because I liked the way I looked naked. Although, to be honest with you, anyone who is 23 looks good naked. Young people are like, “Oh my God, he had pimples.” I’m like, “Trust me, it only gets worse.” You know that expression “It gets better”? No, it only gets worse. But the thing is, self-acceptance can get better. These recent paintings are just about how wonderful it is to be an artist because I can be me. I’ve fought so hard to be me. It takes a long time to be a good painter.

I was taught by abstract painters because figuration was not in vogue. But then I realized nobody was teaching me how to draw, so I decided to take figure-drawing classes, which got me a little bit in trouble in college [as] a painting major. And then I really liked the teacher, who was such a wonderful, gentle person. I’ve already invited him to the dinner at the Morgan Library, him and his wife.

M.H.M.:

What’s his name?

L.Y.:

Chuck Schmidt. He was the official calligrapher to the Kennedy administration, and he also painted astronauts. But I didn’t want to be a realist. It’s interesting to me now that, as a young person, I had an image of what I wanted. But you have to be an autodidact in some ways to be a painter: You read and you go to museums and you look. You talk to your friends, you copy things. You try to figure it out. And I had this intuitive understanding about color. I have no idea where it came from.

M.H.M.:

I always wondered if you are or were ever fond of hallucinogenic drugs.

L.Y.:

I’ve never done hallucinogens. I had a boyfriend who scared me from it. He said, “You should never do that because you’re already too much of a crazy person.” I think people who do drugs want to see things. I already see them.

Maybe I could benefit at some point. I would consider it under the right circumstances. Fortunately, I’ve worked very hard to shake off any traumas I’ve had. When I got to Yale, I got profoundly depressed. I could not get out of bed. And I think I don’t regret what that was, but it made me. … It’s like insomnia. The word “insomnia” will give you insomnia if you say it too late at night. Sometimes even the word “depression” is depressing. It’s like there’s an undertow that you feel like at any time you could be dragged into. But now I know what to do.

M.H.M.:

Did you ever have a major depressive episode after that?

L.Y.:

I had one more. Both were precipitated by losing my identity around myself as an artist. I think being an artist is an extraordinarily privileged life. But it’s not like the privilege of, “I can buy new shoes when I want, and I’ve had the experience where I couldn’t and now I can.” The privilege is being able to make something. There’s a lot of machinery that goes into that, and the way you take care of yourself, and the people you interact with — that all matters. When I got really depressed at Yale, I’d never known someone who went into therapy: They either didn’t have the money or it just wasn’t something they did. So I had no idea how I came to this thought, but I took out the student manual and found this place at health services.

M.H.M.:

What was the episode about? Because you said becoming an art student made you feel free. What was the difference between undergrad and Yale?

L.Y.:

In undergrad, once I got the bug, I was like, “I am your mistress. Whatever it is, this thing, this light that has shined on me, I’m yours. I will sacrifice parking spaces for the rest of my life. I’ll do whatever it takes.” But at Yale, they were very vicious. It was almost like boot camp. They’d get up in your face and call you any possible name they could come up with just to break you down. They make you into jelly and then they build you back up.

And I began to just deteriorate. I really lost it. And the therapist came to the conclusion that I’d taken myself out of my work. And what I should do is put myself back in the work and stop worrying about being criticized. And I literally went to my studio that day and made a painting of someone in bed who looked like they were being buried under the earth. And I felt immediate relief. And it was a template in some ways for how powerful it is to make art that really matters to you as a maker. But also, it really got everyone to leave me alone. When they saw that painting, the message was so loud and clear. I put how I was feeling in the art and I stopped feeling that way.

M.H.M.:

Tell me more about those paintings and how they weaponized your shame.

L.Y.:

I was a young female. I wanted to paint young females. And I was being told that that was the wrong thing to do, that I was never going to have a career if I did that. And I felt like, “This can’t be wrong, because doing this is making me feel elated.” I was willing to take the hit of being an unsuccessful person to make paintings that made me feel alive.

I had a very powerful experience as a pubescent kid, when I started getting nipples. I put Band-Aids on them to hide them. And that memory, of being unable to deal with what my body was saying, is so powerful and so universal. I thought what would be really interesting would be to make paintings where I took young girls and had them staring at you. I painted these eyeballs that were really, really confrontational. They were angry. And then their bodies were doing this thing, popping out here and there. But they were furious. I painted them in sfumato, so they look like they’re disappearing. Because they wanted to disappear. But they couldn’t disappear. They confronted you instead. It was a perfect visual metaphor. I knew I was doing the right work.

M.H.M.:

There’s an essay by Helen Molesworth from a couple of years ago where she’s talking about her embarrassment about liking your work. Other people have said similar things. Does it matter to you who your audience is and what they think they’re looking at?

L.Y.:

The concept of transference is super important to me, to recognize that my work is about both of us. The work is loaded enough that it allows for a lot of interpretation and a lot of misreading, and I like all of that. I started rereading this book recently, “The Silent Woman” (1994) by the great Janet Malcolm.

M.H.M.:

Yeah, I love that book.

L.Y.:

When I went into my real analysis work, I mostly talked about how to make art, so I had to first teach the therapist how to talk about art because nobody really knows how to talk about art. But after a while, we’d have a really great dialogue and, at one point in the ’90s, my therapist gave me this book as a gift. I didn’t recognize myself in the amount of [expletive] that people were saying about me in print. And I don’t believe in not reading stuff about me.

M.H.M.:

You read your criticism?

L.Y.:

Of course. I mean, I think it’s stupid either way: It’s probably a bad idea to read it. It’s probably a bad idea not to. I’m an active person. I’m a doer. So I’m like, “OK, let me just suck it up.” I went from being ignored, which I would say is the worst, to having way too much said. The feedback was so voracious, and a lot of it’s like, “You’re a misogynist. You’re this, you’re that.” One guy said I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth.

I knew I needed to get back to the studio and get quiet and figure out what’s useful and what’s not. I found Malcolm’s book very interesting because it argues, in a sense, that everything’s projection and transference. Who are we really? I’m sure you have people who think the world of you and people who don’t like you. And what do you do with that? Well, it’s about the chemistry between. There’s going to be a chemistry between an artwork and a viewer [too]— either “This is total garbage” or “Oh, this is the best thing I’ve ever seen.” I had to grow accustomed to the fact that that’s something you need to get used to, that you should invite all comers, the haters, the lovers, and that the truth is nowhere and everywhere.

M.H.M.:

Was there a particular work that people were starting to pay attention to — either good or bad?

L.Y.:

Well, people were coming to the studio — because I didn’t have a gallery at the time — and saying things like, “Whoa, you can’t do this.” And one day my best friend from grad school, Jesse Murry, came. And he was really quite a phenomenon at Yale because he was older and he’d already been in New York and he’d already taught art history at Hobart. He’d already written art reviews. He was much more advanced than us on a maturity level and on an intellectual level. Jesse was an oddball, but we became very close. And he said, “You’ve got to have your pussy screwed on straight to make this work.” And I totally understood what he meant. You have to have this clear understanding of who and what you are, both as an artist and as a female, both positive and negative. The first painting I made in that body of work he saw, which I knew was a really good painting, was called “The Gifts” (1990-92). She’s got her eyes locked on you. Her mouth is stuffed with these really tacky flowers and her boobs are sticking out. I even painted the nipples three-dimensionally. It was the worst taste, but I was embracing what I knew about bad taste. I thought, “I need to invite bad taste in here.” And it’s not just wanting to put low culture in. It’s acknowledging, “These were my people. This is my history.” Where’d you grow up?

M.H.M.:

Outside Detroit.

L.Y.:

When you come from a real working-class environment, it’s a group of people that now we have to be ashamed of because they were the people charging the Capitol. And those people, I didn’t know any of them, but I could’ve if I’d stayed where I was from. And it’s uncomfortable to realize this group, the subset of people that we come from, is an actual race that nobody gives a [expletive] about, really. Which is why the politics around it are so weird.

Where I used to go to the library is where people now go to be zombies. But my father was very proud of what he had provided for us. And I do understand that my saying I grew up white trash is an assault on his pride. But then I would say to him, “Oh, Dad, just let me do my own public relations and you do you.”

But this was my experience. I was out there in the jungle. There weren’t those kinds of drugs back then, but we would get into all kinds of scrapes. And it was rough. [But] I loved to read. And I spent so much time reading that some of these kids who are probably dead, or I don’t know them anymore, they’d sort of get upset with me for not hanging out. And I think that there was some sort of angelic force that got me to prefer to read than to endlessly hang out on the corner and try to get older men to buy us malt liquor.

M.H.M.:

What books did you read then?

L.Y.:

A lot of problems I had with a feminist backlash toward me was that it seemed kind of based in not understanding my socioeconomic background. A lot of feminists struck me as coming from an academic background, and I was like, “Yeah, but I’m poor and this is my reality.” From where I stood, we weren’t protected from anything. And I knew it was pulling a pin out of a grenade to paint something like I was painting, like a self-pleasuring woman. But I decided to just explore it to see what would happen. I’m not like, “Yay, me, I made a painting of a bunch of chicks jerking off.”

M.H.M.:

When did you move to New York?

L.Y.:

There’s a picture Matvey took of me sitting in our bedroom at the desk in front of an old-fashioned typewriter, where I fell asleep in my chair applying for jobs. I just never could get a job. I used that image in a painting from the 2024 show in L.A. called “Five Nudes a Painter and a Pieface.” There’s a squatting painter in the foreground who’s nude, but the real painter is the one in the background who has fallen asleep and has not yet become the artist that could make the painting that they’re depicted in.

M.H.M.:

How did you support yourself financially?

L.Y.:

I eventually got a job at the YMCA pool in Hoboken lifeguarding, which I’d done in high school. It was embarrassing to me that I had my master’s degree from Yale School of Art and all these student loans, and I was like, “The only freaking job you can get is lifeguarding?”

Then we moved to Ludlow Street in 1989. I taught myself how to do watercolor and got a job teaching watercolor at night to continuing ed students at Cooper Union. Part of the reason I went to Yale was I heard you could get a teaching job. And I kept applying for teaching jobs everywhere. I still have a huge pile of rejection letters. I joined this thing called the College Art Association, and I would pay my $99 dues, and a pamphlet would arrive in my mailbox with job listings and I would sit there with my yellow legal pad writing down every job. I was willing to move anywhere. But I kept getting turned down. Later I found out, when I did get a crack at a job at N.Y.U., that I’d been sending out letters with a typo in the first line.

M.H.M.:

Oh, no.

L.Y.:

It said, “I applying.” The reason I got a job at N.Y.U. is that, first of all, I knew a guy from grad school who [told the hiring fine arts professor that] I wasn’t … unable to speak the English language. Anyway, teaching was just one of those things I wasn’t meant to do. I taught at Princeton one semester and they offered me a long-term position, and I didn’t take it because I just didn’t want to. As a young artist, I had this very strong image that I was standing with my back to a precipice that was full of rocks that would rip me to shreds if I fell. Like, you step back, you’re gone. Whatever choice I was going to make, I had to remember it’s a long drop behind me. There was only moving ahead.

There are easier ways to make money than to make paintings. But survival is not just socioeconomic, even though it is very much so. It’s also surviving psychically. Wanting to fight for being happy, whatever that means.

I was going to say painting makes me happy, but that sounds like the wrong way to put it. I often will discard what I do, and I don’t always like it, but I love the thing.

M.H.M.:

You like the process.

L.Y.:

Nothing else keeps me as engaged and intrigued. It’s almost like a good relationship, like someone you don’t want to kick out. They don’t bore you or whatever.

M.H.M.:

How does your relationship with your husband figure into that?

L.Y.:

We’ve been together for 40 years. His studio’s in Union Square, and we share images throughout the day, like, “What do you think of this? What do you think of that?”

He was born in Russia, in the Soviet Union, and when the Soviet Union fell, we went all over Eastern Europe on our honeymoon, because he never thought that when he left, he could go back. He’s Jewish and he left in 1980.

M.H.M.:

When did you start making money as an artist?

L.Y.:

I never made much money really at all until I showed with Marianne Boesky. That was the first time I genuinely could live without a second job, and that was like ’96. I was about 34. And one of the sweetest things anybody ever did for me is, one day, Marianne advanced me some money before my show. And I remember going to the bank on Avenue A and seeing there was $20,000 in my account. My husband and I used to just take $10 out. Because you’d bounce a check if you took more than that, right?

But the other thing that was layered over my early years in New York was AIDS. The background of me struggling to get to my studio in between teaching or lifeguarding was tending to Jesse Murry’s health. Jesse found out that he had H.I.V. in grad school, and I promised him I wouldn’t leave his side, and I didn’t know what I was in for. But I will say that it was one of the most important — hard but important — things that happened to me. One of the reasons Matvey and I wanted to get married when we did is that I wanted Jesse to be at the wedding, and I knew he was going to die.

But the intensity of going to the hospital and watching, not just Jesse, but all those people lose their lives was a major part of my memories of the ’90s. And when he died, I was actually having my first show, at Elizabeth Koury Gallery. It opened January 1993, and Jesse died that week.

M.H.M.:

How do you think he impacted you as an artist? And how do you think taking care of him at the end of his life impacted you as an artist?

L.Y.:

Well, I felt very seen by him. In grad school, when I was very depressed, he told me how lucky I was to be depressed. Because he’d been depressed himself. He told me, “You’re going to see one day, this is going to create much more depth in you.” And he was not wrong.

Jesse also came from a very poor background, and at Yale we were the only two students who’d taken the grand tour of Europe to see paintings in person: the two most unlikely people to have been able to do that. When I was a student at Tyler, I studied in Italy, which was a life-changing experience. We went to Venice, and it was after hours, and I followed this teacher into this church because I was actually following a guy who was following her. Naughty art students after hours. I had a crush on a guy, he had a crush on the art history teacher.

But what I loved about the [San Zaccaria Altarpiece] is there’s no story. I realized this was a painting about the afterlife because all these saints lived in different places and at different times, and they wouldn’t have been able to have a conversation, because they didn’t even speak the same language. And they all were being represented in this beautiful light. They’d all died by being tortured. And the painting was of the moment when the pain ended, and I just stood in front of it and cried.

Of course, as an 18- or 19-year-old, I didn’t have the skills or the ability to do one tiny thing with what I’d seen. And I moved on with my work, forgetting about the painting, putting it in the back of my mind. I’ve come to realize that the back of one’s mind is a pretty powerful place. You have to fill it up. Read, look. Don’t worry about what you’re going to do with it. Just fill her up. It’s like driving around with a lot of extra gas.

So I’m at Yale and I was past my crisis, and I started making these really weird paintings of two or three figures standing in an interior, not looking at each other and not talking. And Jesse comes to my studio and looks at them and says, “You know what these remind me of? The sacred conversation [painting] by Giovanni Bellini.” I almost [expletive] the bed. I hadn’t talked to him about that previously. So when I say he saw me, I was constantly startled by his recognition of me and what I was trying to do.

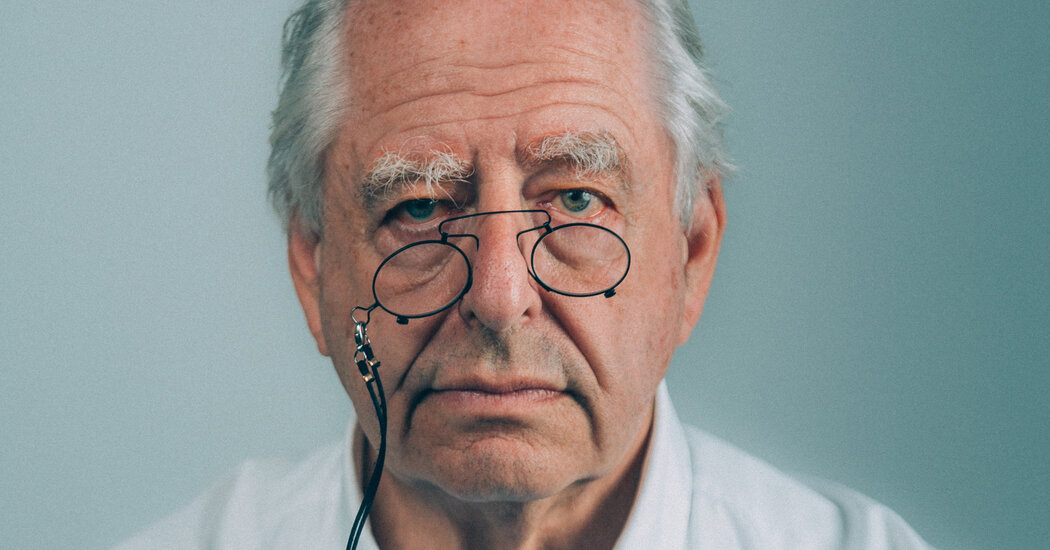

Photo editor: Esin Ili Göknar. Digital production and design: Danny DeBelius, Chris Littlewood, Coco Romack, Carla Valdivia Nakatani and Nancy Wu